The curatorial and editorial project for systems, non-

Agnes Martin exhibition at Tate Modern

A review by Alan Fowler

June 2015

©Copyright Patrick Morrissey and Clive Hancock All rights reserved.

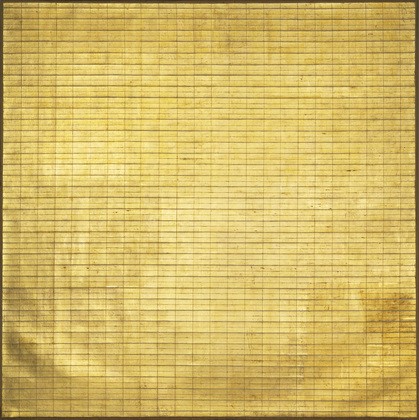

To what extent is it necessary to know about an artist’s life, beliefs and intentions in order fully to appreciate the art they produce? The question is triggered by the retrospective exhibition of the American abstract artist, Agnes Martin (1912 – 2004) now running at Tate Modern. The two dominant features of Martin’s work were the foregrounding of grids in the earlier part of her career, and later the display of horizontal and vertical bands of colour. Grids and orthoganality immediately bring to mind the essential characteristics of constructivist abstraction and the kunst konkret of De Stijl and Max Bill. The grid, for example, is a structuring element in constructive abstraction, and generates visual qualities of precision, clarity and rationality. But these were not the qualities which Martin sought to project. She was concerned primarily with a picture’s emotional impact, and her statements about her philosophy and artistic intentions – set out in the exhibition’s labels and catalogue essays – make it clear that a constructivist reading of her work would be wholly misleading.

Agnes Martin, On a Clear Day, 1973, 371 x 372

Taking a firmly non-

Agnes Martin, Friendship, 1963, 190.5 x 190.5

Some commentators have categorised her work as minimalist, and Donald Judd was certainly an admirer, but this is not a description she agreed with, as she criticised minimalists for being too cerebral or intellectual in their descriptions and explanations of their work. She always maintained that her own work evolved intuitively and was essentially an expression of the emotional mind, saying: “It’s not about facts, it’s about feelings”.

In any event, it is difficult to see as minimalist a work as complex as The Islands of 1961 in which the central portion is based on a grid of 96 lines vertically and horizontally, creating over 9000 cells, within which are 3072 minute rectangles, in each of which are two tiny white ovals. (The density of lines in this work fail to show in any small reproduction, and even the .large plate in the catalogue is unsatisfactory in this regard).

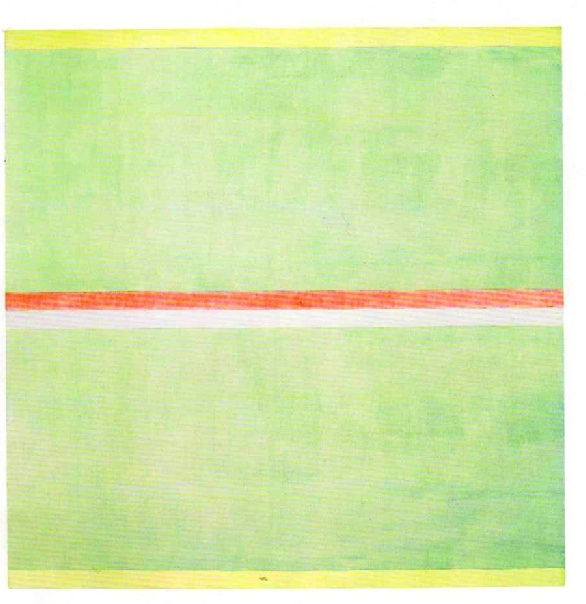

Even in the geometrically simpler colour works of her later period, a minimalist

approach would not have resulted in a work such as Gratitude of 2001 with its six

colour bands in four colours. It is noteworthy that the odd titles she gave to this,

and many other of her works, do not refer to any formal characteristics of the imagery

– and it must be admitted that most these titles add little or nothing to the viewer’s

understanding of the works themselves. Titles such as Friendship, The Peach or Drift

of Summer bear no obvious relationship to the grid paintings to which they are applied,

nor do Happy Holiday or I Love the Whole World throw any light on the origins or

artistic intent of such-

Agnes Martin, Gratitude, 2001, 152.4 x 152.

The artists (all American) with whom Martin saw herself as being most closely associated,

and with whom she fraternised while living in New York, were the post-

Be that as it may, perhaps Martin’s troubled mental health, her preference for solitude

and the many years she spent living in her isolated log cabin in the New Mexico desert,

must surely provide some explanation for the nature of her work. She battled with

schizophrenia, found refuge in the philosophy of Buddhism, and sought for the solace

of Zen tranquillity. The imprecision of the lines in her grids, and the subdued,

non-

She does seem to have been influenced by the visual nature of her New Mexico surroundings,

although her form of abstraction was not the landscape-

Agnes Martin, Untitled, 1980, 600 x 589

She set out her own thoughts as to how a viewer should approach her work in a comment she made about a portfolio of 30 screen prints (entitled On a Clear Day) which consisted of a set of relatively simple variations of a 10 x 10 grid. “These prints”, she wrote, “express innocence of mind. If you can go with them and hold your mind as empty and tranquil as they are, and recognize your feelings at the same time you will realize your full response to this work”. Put another way, it seems she was commending contemplation rather than analysis as the best mode of looking at her work.

Viewing the exhibition as a whole, the conclusion is that the show can be approached

in two very different ways. One is to look at the whole range of Martin’s work within

the context of the artist’s beliefs and her long and sometimes troubled life. Speculation

about the possible interaction between her life experience and her art may then be

of significant interest. The other way is to set aside all possible personal and

psychological influences within Martin’s oeuvre and view each work as a self-

As a comprehensive and excellently planned and presented retrospective, the show

is very successful in providing for a biographical approach. The fact that much of

her writing about her art is not easy to relate to the visual characteristics of

the works themselves may actually encourage a close and enquiring attention – trying

to solve the puzzle, as it were. But the exhibition’s strength in term of its comprehensive

display and documentation forms a weakness for the viewer who wants to experience

the works simply and solely as self-