The curatorial and editorial project for systems, non-objective and reductive artists

working in the UK

Cluster | Anna Fairchild, Sian-Kate Mooney and Lucy Renton

Supported by The Broadway Gallery and Letchworth Culture Project, Letchworth, 21

Oct – 20 Nov 2021

A review by John Stephens

©Copyright Patrick Morrissey and Clive Hancock All rights reserved.

The slow demise of urban centres has been a worry for local councils for some time,

and has been hastened somewhat by the pandemic. Shops and businesses, often well-known

high street brands, have very visibly been leaving empty premises on high streets

up and down the country. Culture has often become a remedy for this blight, and

so it has been with Letchworth’s Broadway Gallery, set up by Letchworth Garden City

Heritage Foundation, with its growing reputation for nationally significant shows.

But the Foundation is also responsible for the initiative of setting up the Letchworth

Culture Project, which aims to encourage proposals from local arts, culture and heritage

communities to take advantage of some of the town’s empty properties and retail spaces.

Grasping the opportunity, Hitchin-based artist Anna Fairchild conceived and curated

Cluster, an exhibition involving herself and two other artists: Sian-Kate Mooney

and Lucy Renton, using a vacated shop close to the city centre as its venue. It

was an ideal exhibition space; a plain grey concrete floor, large expanses of white

walls and a wide, glazed double frontage letting in plenty of light and affording

visibility into it on darkening late autumn afternoons and evenings.

For conservative Letchworth town centre, this was no conventional exhibition. What

was being shown was three-dimensional in nature, but it wasn’t traditional sculpture.

And, whilst on the face of it there was little that immediately struck the viewer

as a common thread between the three artists, their practices appearing markedly

divergent from each other, closer links are there to be explored.

In describing her approach to colour, Lucy Renton drew attention, in her artist’s

talk, to her wanting to escape the line-bounded plane, which had been so much part

of her art education. Punkt, Linie, Fläche (point, line, plane), the basis of a

key art educational principle, springs to mind. These were the essential visual

elements identified by Kandinsky and Klee, Bauhaus teachers in the first half of

the 20th century, and also used extensively, later in the century, in so much teaching

of art and design in Britain. Why do I mention this? Because I think a key link

between the three artists is in taking the next logical step: that from plane to

form.

Because in fact, these artists have all three worked with flatness in one way or

another. And, independently of each other, they’ve established a transition from

flatness to three dimensions, doing so by exploiting their materials and processes

in inventive and imaginative ways, in large part driven by the conceptual demands

of what it is they’re trying to say. And in no way, I should hasten to add, have

they taken a purely formalistic approach.

The ingenuity shown by the artists has - perhaps inevitably - something to do with

where they came from, both artistically and professionally. Anna Fairchild trained

as a sculptor and having travelled extensively, has developed a diversity of practices:

as well as sculpture, these include drawing, printmaking, photography and video.

Lucy Renton trained as a painter and printmaker, and Sian-Kate Mooney’s early training

and professional practice as a fashion designer and maker has latterly fed into her

fine art practice. All three have over time acquired wide cultural interests that

go beyond the artistic. Going into a little more detail about the individual works

should, I hope, clarify my contention.

Anna Fairchild’s principal material is Jesmonite, a form of plaster, which she pours

onto surfaces and lifts off once it has hardened. The hardened plaster picks up

details from the surface such as any contours, deposits or markings, and these then

become an integral part of the work. Essentially, it’s a form of casting; whatever

is picked up in the process becomes part of the work. It isn’t always incidental,

it’s often pre-conceived, and sometimes, as in the case of her pieces in this show,

a combination of both.

Anna Fairchild, Hyphae - Call, 2021

Anna Fairchild, Hyphae - Call and Response, 2021

Hyphae – Call introduces us to Fairchild’s working methods as well as to her divergent

interests in aspects of architecture and nature. Two contrasting visual elements

coexist here. The first is an architectural-looking ‘armature’ with a concave surface

supporting smaller biomorphic elements. You’re invited to figure out how it’s been

put together, because the smaller forms aren’t stuck on, they’re an integral part

of the whole. The piece seems, in fact, to have been made in one casting, the Jesmonite

having been poured over a semi-cylindrical former or mould that was once flat. It’s

been deeply scored in a vertical direction, and more lightly in a horizontal direction,

and made into a semi-cylindrical former.

As it was poured over, the liquid Jesmonite has picked up these scorings as ridges

of varying relief, along with stains of colour that became visible when it was removed.

The surface of the former has been perforated with rectangular openings, rather

like windows, and it rests on a flat surface. In the process of pouring, the Jesmonite

appears to have trickled through some of these ‘windows’ and spread out on the lower

flat surface. It’s a process that’s taken time and artistic experience to evolve.

The process must envisage the ‘negative’ outcome, and in this respect, it has made

for an unusual looking, but evocative and highly original work. As said, there’s

an allusion to architecture, with the biomorphic elements seeming to grow like fungal

protuberances from the ‘architecture’ thereby upsetting a suggested scale that belies

its actual size. Herein lies the intelligence of its making.

Similarly made, with an equally evocative outcome, is Hyphae Call and Response which

exists as two separate pieces in a kind of strained and aloof diptych relationship.

Anna Fairchild, Mycelium Blooms, 2021

Also consisting of two separate pieces set in relationship with one another is Mycelium

Blooms. Here, one part is set on the floor just below the other, which is wall-mounted.

Both have been made with the same Jesmonite pouring process. There’s a diffuse meandering

swathe of orange and brown pigment running bottom to top of each of the concave surfaces,

giving a suggestion of what might have been a continuous flow from one to the other,

were it not for the gap between them.

But unlike the two Hyphae pieces, this has not been made in one pouring. In this

piece the plane-to-form transition has taken on another articulation. The same concave

surfaces are present, supporting similar biomorphic elements, but the difference

lies in there being an articulation of more than one of these concave planes. Working

out how this was achieved is a puzzle. The pieces appear to have been made individually

and brought together by an additional pouring of Jesmonite, creating a more uncomfortable,

more provocative outcome, with surfaces seeming to collapse in on one another and

then open out again, creating tight, claustrophobic internal spaces.

Sian-Kate Mooney, A La Mode, 2021

In contrast is Sian-Kate Mooney’s single piece: A La Mode, which with its pliant

fabric material has a powerful allusion to her past career as a fashion designer

and maker. But this piece, too, has its origins in flatness. Mooney has used blue-striped

fabric, reminiscent of that frequently used by Daniel Buren in his minimalist installations,

except that here, the stripes have been hand-painted by the artist, and with their

inherent regular rhythm they emphasise the flatness of the otherwise white canvas

fabric. Through her working processes the fabric ultimately assumes complex three-dimensional,

syncopated forms.

The piece is shown in two ways: the first as a garment, comprising jacket and trousers

clothing a mannequin. We see the fabric as what it is, remaining intact as ‘garment’

fabric, shaped around the form of the mannequin, with the stripes having a diagonal

orientation, thereby giving differing directional indications and dynamics. But emerging

from one of the sleeves, the fabric assumes a completely different character. It

extends way beyond the dimensions of the figure - scrunched and pleated in a kind

of ever-increasing time-lapse rhythm of movement, at first chaotic, then gradually

becoming more regular in its syncopation. It appears to assume a regular wing beat,

wanting to fly off, dragging the grounded figure with it.

Sian-Kate Mooney, Muster & A La Mode: detail

A la Mode was the outcome of an Arts Council England-funded project that had as its

aim the investigation of a relationship between painting and garment-making, and

as it turns out has achieved something of the quality of a three-dimensional painting.

The second manifestation of the piece in the show is as a photograph (above), in

which the ‘garment’ is worn by the artist as part of a performance, set against the

rather splendidly austere 60s-built Arlington House in Margate. The brutalism of

the architecture acts as the perfect foil for the visual dynamics of the piece, which

the static display is only able to do in a limited way.

The articulation of flat materials has for some time been a preoccupation for Sian-Kate

Mooney. She’s previously worked with bituminised corrugated roofing materials, recycled

garment fabric and striped industrial towelling materials, but also with more bulky

materials such as clay, wax and soap, often using these as ways of stiffening fabric.

She’s used physical processes that involve scrunching, folding, bending, rolling,

binding and bundling, all of which have been used to transform flat materials into

three-dimensional objects. A La Mode comes as a culmination of these investigations

in this very articulate work.

It’s in Lucy Renton’s work that the relationship between flatness and three dimensions

is perhaps most apparent, and it was her work that directed my perception of it.

Listening to her talking about her work, I understood that she has been driven

by the desire to re-establish the modernist notion of the primacy of colour over

line. And of course, colour in modernist painting is closely associated with flatness,

so her work really articulates a significant moving on from this. Originally a painter

and printmaker, Renton’s interests have broadened to an investigation of domestic

decoration and its association with colour. She has a particular interest in the

department store, and the fabrics and surface coverings available in catalogues and

in sales displays, on furniture and soft furnishings; an interest that, through her

travelling, has extended to the markets and bazaars of the Middle East. It’s an interest

shared by Yinka Shonibare, an artist she has come to admire, and through him, she

has come to see how fabric, with its patterning and colour, can symbolise different

societies, domestic environments and histories.

It is tempting, but would be entirely gratuitous, to describe her work as decorative:

far from it, she uses materials that might have a decorative association, but this

is not what her work is about. She was strongly affected by a short residency in

Istanbul a few years ago; she saw the way in which refugees from Syria were making

makeshift homes on the outskirts of the city, and was intrigued by the way in which

fabrics could be simultaneously associated both with opulence and with poverty. The

simple use of cheap fabrics affords a sense of homeliness in refugees’ makeshift

dwellings, while in in more wealthy households they can enhance a feeling of opulence.

Ironically, there’s a commonality between these seeming opposites that has given

Mooney new opportunities to celebrate colour and pattern.

Fritz does just this; it comprises what appears to be a long run of predominantly

red fabric patterned with small, ice blue and chrome yellow rectangles and bordered

by narrow bands of natural fabric. On closer inspection it turns out not to be acquired

fabric; it is in fact very fine linen canvas, that favoured by portrait painters

for its fine weave, allowing for the painting of fine detail. And the artist has

painted all the elements herself, adding self-made tassels and fringes cut with scissors

into the canvas. Pinned to the wall, the piece hangs loosely onto a low-level varnished

wooden shelf to which it is attached with pale blue cords, like a stair carpet. It

then falls to the floor where it is again attached with blue cord, then runs out

onto the floor, ending with a fringe of blue and yellow, again scissor-cut. The

whole could be part of a tasteful interior décor scheme, or makeshift seating outside

a refugee’s dwelling: a reminder of home.

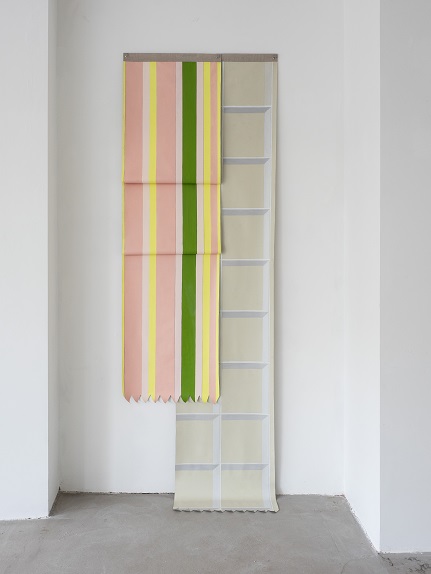

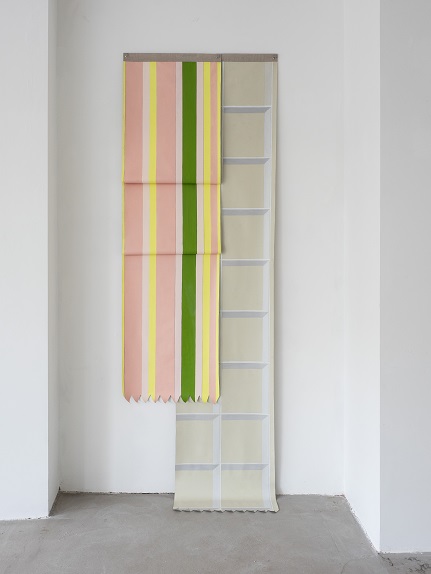

Lucy Renton, Juliette, 2021

Perhaps having more the feel of a display of interior fabrics is Juliette (Fig. 7)

a two-part piece again made using fine linen portrait canvas painted and cut by the

artist (the fine canvas allows for cutting without leaving a frayed edge). Painted

in vertical pink and yellow candy stripes with a strong line of green, the wide strip

of linen hangs, its flatness denied by two horizontal folds. It partly obscures

another piece of painted canvas which hangs down onto the floor. This part is flat,

but is given the appearance of three-dimensionality by the trompe l’oeile painting

of what appears to be an elongated window casement.

But the illusion of three-dimensionality is cancelled by the way the canvas trails

on the floor and becomes flat fabric again. In a sense, the flatness/three-dimensionality

device of each part is cleverly reversed in the other. Unlike Fritz, this piece signifies

no ambiguity of location; instead, with some of the fabric assuming three-dimensional

characteristics and some of it being just an illusion, it’s more a play between the

idea of reality and illusion - often so much a part of what interior fabrics do.

The use of seemingly disparate elements to make visual statements is very much part

of Lucy Renton’s visual language. So it is with Bubbles; a vertical piece of linen

lies flat on the wall plane, hanging down to the floor, with its ends running out

briefly onto the floor. It has two completely different surfaces, divided by a vertical

pleated curtain of pink canvas that is drawn together in the middle with a yellow

bow which appears to stand free in front, but which is in fact pinned to the wall

at the top to hold it in place. The left-hand side is painted yellow with a barely

discernible grid of darker yellow rectangles, while on the right there are small

discs of colour: shades and tints of greens, blues and pinks, painted or possibly

screen-printed in random repeated groups suggestive of fabric printing. On the face

of it, this suggests both Renton’s delight in what might be deemed cheap fabrics

and their simple arrangement, alongside the more painterly problem of using the three

primary colours, red, yellow and blue, in a more intellectual artistic exploration

of her stock devices, suggesting a play between flatness, illusion of depth and actual

depth.

Although my original contention was that the link between the three artists was to

do with the transition from flatness to three-dimensionality, I did not want to give

the impression that I saw this as a purely formal consideration. How I would like

this contention to be understood now is that although it is an understanding deeply

rooted in the artists’ individual practices, it is the ingenuity in their choice

and handling of materials, along with their conceptual originality, and the ways

in which those materials and processes have been used to articulate their ideas,

that marks out the work of these three artists.

Letchworth Garden City Heritage Foundation must see Anna Fairchild’s very thoughtfully

conceived and curated gem of an exhibition as a vindication of its creation of the

Letchworth Culture Project.

John Stephens

December 2021

Photographs by Andrew Moller

Instagram: _andrewmoller

Lucy Renton, Bubbles, 2021